Framingham Risk Score Calculator Pdf To Jpg

Background Cardiovascular disease is associated with major morbidity and mortality in women in the Western world. Prediction of an individual cardiovascular disease risk in young women is difficult. It is known that women with hypertensive pregnancy complications have an increased risk for developing cardiovascular disease in later life and pregnancy might be used as a cardiovascular stress test to identify women who are at high risk for cardiovascular disease. In this study we assess the possibility of long term cardiovascular risk prediction in women with a history of hypertensive pregnancy disorders at term. Methods In a longitudinal follow-up study, between June 2008 and November 2010, 300 women with a history of hypertensive pregnancy disorders at term (HTP cohort) and 94 women with a history of normotensive pregnancies at term (NTP cohort) were included. From the cardiovascular risk status that was known two years after index pregnancy we calculated individual (extrapolated) 10-and 30-year cardiovascular event risks using four different risk prediction models including the Framingham risk score, the SCORE score and the Reynolds risk score. Continuous data were analyzed using the Student’s T test and Mann–Whitney U test and categorical data by the Chi-squared test.

A poisson regression analysis was performed to calculate the incidence risk ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals for the different cardiovascular risk estimation categories. Cardiovascular disease is associated with major morbidity and mortality in women in the Western world. Women are less likely to receive appropriate cardiovascular preventive care compared to men and heart disease in women is not always recognized as a major health care concern. Several epidemiological studies have demonstrated the association between hypertensive pregnancy disorders and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in later life ,. Subsequently, it has been suggested that pregnancy may act as an early natural “ stress test” unmasking underlying defects and thereby identifying women at high risk for cardiovascular disease in later life. Worldwide, different risk prediction models have been developed for individual risk prediction of cardiovascular disease in both apparently healthy men and women ,.

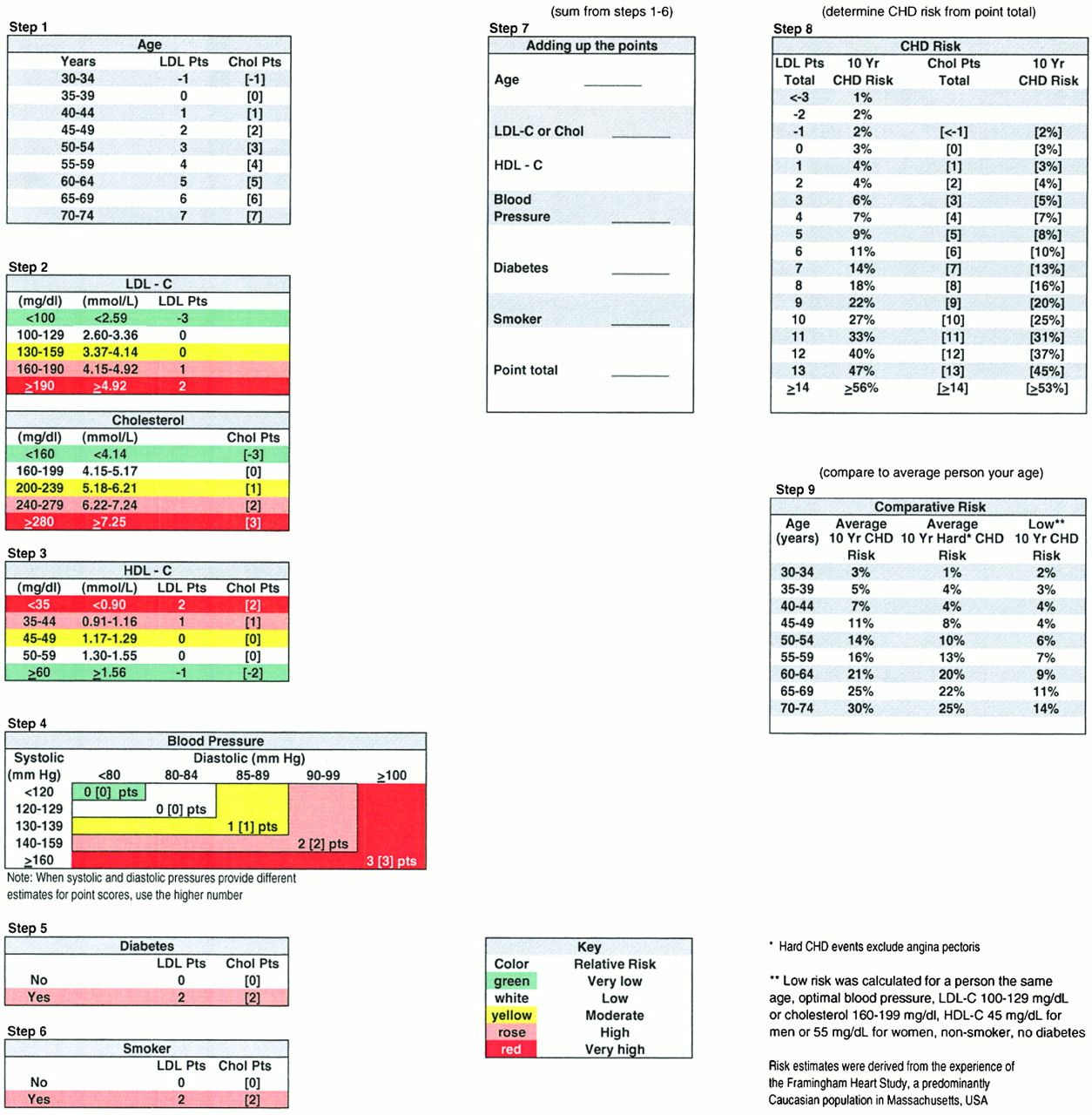

Currently, the Framingham risk score is the most compared score in literature and widely used in North American countries , while the systematic coronary risk evaluation (SCORE) score has been advised by the European guidelines. In spite of the existence and use of several risk prediction models, it remains a great challenge to determine which specific woman is at high risk for cardiovascular disease, especially in young women. Obstetric history, e.g. Hypertensive pregnancy disorders, is not included as a variable in cardiovascular risk prediction models. However, obstetric history may help to identify women, who are at high risk for cardiovascular disease in later life; they may benefit from early cardiovascular risk screening after their complicated pregnancy together with subsequent individual cardiovascular risk prediction and primary prevention programs ,. Showed that women, who perceive themselves at risk for cardiovascular disease and know the goals for prevention, are motivated to take action toward a heart healthy life style ,. In the present study, we assess cardiovascular event risks in women with a history of gestational hypertension or preeclampsia at term using four previous described validated cardiovascular risk prediction models, including the 10-year Framingham risk score, the 30-year Framingham risk score, the 10-year estimation by the SCORE score, and the 10-year estimation by the Reynolds risk score.

According to the European cardiovascular risk factor management guidelines for young women with elevated risk factor levels , we extrapolate the 10-year cardiovascular disease risks as if the woman is 60 years old. The aim of this study is to compare these estimated (extrapolated) 10-year and 30-year cardiovascular disease risks between women with a history of term gestational hypertension or term preeclampsia and women with a history of term normotensive pregnancies, in order to improve assessment of reliable cardiovascular risk estimation for the long term cardiovascular disease outcome in relatively young women. Participants We studied 300 women who had delivered in the Netherlands between 2005 and 2008, with the diagnosis term gestational hypertension or term preeclampsia after 36 weeks' gestation and 94 healthy control women after uncomplicated term pregnancies. The women were invited for participation in the current follow-up study on cardiovascular event risk estimation.

We enrolled women with a history of term gestational hypertension or term preeclampsia from the Hypertension and Pre-eclampsia Intervention Trial At Term (the HYPITAT study). Control women were friends of the patients or women from midwifery practices from three different locations in the Netherlands (Groningen, Leiden and The Hague) and they were required to have only previous uncomplicated normotensive pregnancies.

Between June 2008 and November 2010, a total of 300 women with a history of term gestational hypertension or term preeclampsia and 94 women with a history of normotensive term pregnancies were included in this follow-up study. Of the eligible 751 women with a history of term gestational hypertension or term preeclampsia, 168 women declined participation in the follow-up study, 6 women refused blood drawing, 175 women were lost to follow-up, 101 women were pregnant or lactating and 1 woman had died in a car accident. At index pregnancy, women with term gestational hypertension or term preeclampsia were more often nulliparous, had higher body mass index at the first antenatal visit, higher systolic and diastolic blood pressures at the first antenatal visit, lower gestational age at delivery and lower birth weight compared with women with a history of normotensive term pregnancies (Table ). At 2.5 year follow-up women with a history of term gestational hypertension or term preeclampsia were more often primiparous, used more antihypertensive medication, and had higher body mass index, higher systolic and diastolic blood pressures and higher waist circumferences compared with women with a history of normotensive term pregnancy. There were no significant differences in age, elapsed time since delivery and smoking rates (Table ). Characteristics HTP cohort NTP cohort p value (n=300) (n=94) Maternal age at delivery (years) 31 (28–35) 31 (28–34).82 Ethnic origin: Caucasian 273 (89%) 94 (95%).14 Other 30 (10%) 5 (5%) Unknown 3 (1%) 0 (0%) Nulliparous 211 (69%) 30 (30%).

Characteristics HTP cohort NTP cohort p value (n=300) (n=94) Age at follow up (years) 34 (30–37) 34 (31–37).80 Time elapsed since delivery (years) 2.4 (2.2-2.7) 2.5 (2.2-2.9).54 Primiparous 134 (44%) 21 (22%). Figure illustrates the risk percentages of developing general cardiovascular disease within 10 years in women with a history of term gestational hypertension or term preeclampsia and women with a history of normotensive term pregnancies at current age, calculated with the Framingham risk score.

At current age, 16 women (5%) with a history of term gestational hypertension or term preeclampsia had a 10-year general cardiovascular disease risk of 5%, compared with no women (0%) with a history of normotensive pregnancies, p=.02. Figures A and B show the risk percentages of developing general cardiovascular disease within 10 years (Figure A) and the different risk categories of the 10-year prediction of developing general cardiovascular disease calculated with the Framingham risk score (Figure B) of hypertensive term pregnancy women and normotensive term pregnancy women after extrapolation of their age to 60 years. Poisson regression showed that women with a history of term gestational hypertension or term preeclampsia, compared with women with a history of normotensive term pregnancies, had a 2.5-fold higher extrapolated risk of 5% (p10% (p=.001, IRR 5.8 95% CI (1.8 - 19)) to suffer from cardiovascular disease within 10-years. After adjustment for parity and current BMI, women with a history of term gestational hypertension or term preeclampsia had still higher extrapolated cardiovascular event risks of 5% (p 10% (p=.01, IRR 5.0 95% CI (1.6 - 16)) compared with women with a history of normotensive term pregnancies. Figure 2 10-year Framingham risk score extrapolated to the age of 60 years. 10-Year Framingham risk scores (%) extrapolated to the age of 60 years of women with a history of uncomplicated normotensive pregnancies (NTP women, dotted bars).

The top and bottom of each box correspond to the 75th percentile and 25th percentile, respectively. The whiskers (t bars) on the top and botttom denote the 90th percentile and 10th percentile, respectively. Division into 4 different risk categories (0 - 5%, 5% - 10%10% - 20% and 20%). 10-Year risk of estimation of overall cardiovascular disease risk according to the Framingham Heart Study algorithm based on the following risk factors, ie.

Age, smoking, systolic blood pressure, HDL cholesterol, total cholesterol. 30-year full cardiovascular disease risk prediction by the Framingham risk score Figure A illustrates the risk percentages of developing overall cardiovascular disease within 30 years in women with a history of term gestational hypertension or term preeclampsia and women with a history of normotensive term pregnancies at current age, calculated with the Framingham risk score. Figure B illustrates different risk categories of the 30-year prediction of developing general cardiovascular disease calculated with the Framingham risk score at current age. Poisson regression analysis showed that women with a history of term gestational hypertension or term preeclampsia, compared with women with a history of normotensive term pregnancies had an almost 3-fold higher of 10% (p. Figure 3 30-year Framingham risk score at current age. 30 - Year Framingham risk scores (%) at current age of women with a history of gestational hypertension or preeclampsia at term (HTTP women closed bars) and women with a history of uncomplicated normotensive pregnancies (NTP women, dotted bars). The top and bottom of each box correspond to the 75th percentile and 25th percentile, respectively.

The whiskers (t bars) on the top and botttom denote the 90th percentile and 10th percentile, respectively. Division into 4 different risk categories (0 - 5%, 5% - 10%10% - 20% and 20%). 30 - year risk of estimation of full cardiovascular disease risk by the Framingham Heart Study algorithm based on the following risk factors, ie. Age, smoking, systolic blood pressure, HDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, treatment for hypertension and presence of diabetes. 10-Year fatal cardiovascular disease risk prediction by the SCORE score and 10-Year global cardiovascular disease risk prediction by the Reynolds risk score Mean (SD) 10-year cardiovascular disease risk predictions and different risk categories calculated by the SCORE score and the Reynolds risk score are shown in Table. Women with a history of term gestational hypertension or term preeclampsia had significant higher mean risks calculated by the SCORE score and the Reynolds risk score compared with women with a history of normotensive term pregnancies.

Framingham Risk Calculator Acc

Furthermore, women with a history of term gestational hypertension or term preeclampsia were more often represented in higher risk categories. IRR incidence risk ratio. CI confidence interval. NTP women with a history of normotensive term pregnancies. HTP women with a history of term gestational hypertension or term preeclampsia.

Sub-analyses of the hypertensive term pregnancy cohort We divided the hypertensive term pregnancy cohort (n=300) in a primiparous subgroup (n=134, 44%) and a multiparous subgroup (n=166, 56%) 2.5 years postpartum. Furthermore, we subanalysed women with a history of gestational hypertension at term (n=225, 75%) and women with a history of preeclampsia at term (n=75, 25%) and women with (n=93, 31%) or without (n=207, 69%) severe gestational hypertension or severe preeclampsia during their index pregnancy.

No significant differences were found between the subgroups in the prevalence of hypertension 2.5 years postpartum, biochemical cardiovascular risk factors 2.5 years postpartum and in the estimated 10- and 30 year Framingham cardiovascular event risks. In this longitudinal follow-up study, we found that women with a history of term gestational hypertension or term preeclampsia have an increased 10-year cardiovascular disease risk at current age and after extrapolating the age to 60 years at least two years postpartum. Furthermore, an increased 30-year cardiovascular risk at current age was found in women with a history of term gestational hypertension or term preeclampsia. Risk prediction models Screening and treatment of cardiovascular disease should target women at high risk rather than at women with a single elevated risk factor. Many risk prediction models have been developed the last three decades to estimate individual cardiovascular risk.

The Framingham Risk Score was the most influential multivariate risk predictor of developing cardiovascular disease in the future and this algorithm has been most often compared by other studies ,. The Reynolds Risk Score was developed in women adding CRP and parental history of early myocardial infarction before the age of 60 years as independent risk variables in a female cohort and reclassified 40%-50% of women who were predicted by the Framingham risk score to be at intermediate risk into higher- or lower risk categories. The SCORE equation has been validated for the European population and has been recommended by the Third Joint European Task Force on cardiovascular prevention in Europe. This risk score focuses at fatal total cardiovascular risk rather than at fatal coronary heart disease. Other prediction models were mostly designed and developed for men and therefore not considered for this study. The QRISK score was developed using a population- based clinical research database in the UK incorporating ethnicity, deprivation and other clinical conditions in the algorithm , , resulting in more accurate quantification of risks in south Asian women compared to the Framingham risk score. However, participants in our study were predominantly Caucasian women and adding ethnicity to the risk estimate was considered to have no additional value for risk estimates.

Therefore, we did not use the QRISK score for our study. In 2012, Siontis et al. Undertook a meta-analysis to compare established risk prediction models for cardiovascular disease. They did not reach robust conclusions about the best risk prediction model or the ranking of performance of different models.

An important question rises: which algorithm or model is best suited for women with a history of hypertensive pregnancy disorders at term to accurately estimate their future cardiovascular risk? Unfortunately, we can not answer this question with our present study results. All four algorithms showed a significantly higher risk in hypertensive term pregnancy women. This is understandable, because the four scores are mostly based on equivalent cardiovascular parameters and these parameters were significantly higher in the hypertensive term pregnancy cohort compared with the normotensive term pregnancy cohort. However, the definitions and cardiovascular endpoints between the four risk prediction models differ. Only the Framingham Heart Study provides a 30-year risk prediction model.

This might be the most useful prediction model for our relatively young study cohort, as age remains the most important parameter in cardiovascular risk prediction models and extrapolation is not necessary in this model for our relatively young cohort. Furthermore, the Framingham 30-year risk score focuses at cardiovascular morbidity and mortality rather than at cardiovascular mortality alone (SCORE score), which seems important in young women. Morbidity caused by non fatal cardiovascular events is not only disabling for young women, but it is also the major economic burden for the health care system and society. Young women might benefit from early screening and prevention and it might be cost-effective. However, we have to keep in mind that the longer the prediction period, the less accurate the prediction will be for an individual, as the nature of the design does not account for individual changes in risk factor levels that could have taken place during the course of follow-up.

Comparison with other studies Three other studies previously assessed cardiovascular risk scores in women with a history of hypertensive pregnancy disorders. Fraser et al. reported significant higher mean Framingham 10-year cardiovascular risks of 4.6% (0.15) in women with a history of gestational hypertension, 5.1% (0.41) in women with a history of preeclampsia compared with 3.6% (0.06) in women with a history without hypertensive pregnancy disorders. These risks were higher compared with the 10-year cardiovascular risks (at current age) in our study in women with a history of hypertensive pregnancy disorders. This might be explained by two differences. First, Fraser et al. Included not only women with a history of hypertensive pregnancy disorders at term but also women with a history of preterm hypertensive pregnancy disorders, which are known for their higher risk of cardiovascular disease later.

Second, the follow-up period of 18 years by Fraser et al. Was longer compared with our follow-up period of 2.5 years, which resulted in a significant age difference between the two studies and, per definition, in lower estimation of cardiovascular risk in our study. reported comparable 10-year cardiovascular event risks as our study.

However, they included women with a history of both preterm and term preeclampsia and they had a shorter follow-up period of 1 year. Mongraw-Chaffin et al. prospectively investigated the contribution of hypertensive pregnancy complications on the risk of cardiovascular disease death. They found that women with a history of preeclampsia with onset after 34 weeks’ gestation, after a follow-up period of 30 years and with a median age of 56 years, had a cumulative cardiovascular disease death survival of 98.3% and women without a history of preeclampsia had a cardiovascular death survival of 99.3%. We calculated a mean 10-year fatal cardiovascular disease risk of 1.2% (0.5) in our hypertensive term pregnancy cohort after extrapolating the age of each participant to 60 years. This is a slightly lower risk compared with the 1.7% cardiovascular death risk published by Mograw-Chaffin et al. An explanation might be that Mongraw-Chaffin studied women with preeclampsia who delivered after 34 weeks’ gestation, while we included women with both gestational hypertension and preeclampsia after 36 weeks’ gestation.

These differences in both gestational age and hypertensive disorder might explain the small discrepancy between the risks. A second explanation might be that hypertensive pregnancy disorders are independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease later in life and as a consequence current cardiovascular risk prediction models underestimate women’s cardiovascular disease risks, as obstetric history is not included as a variable in the models. Further large prospective studies have to evaluate whether hypertensive pregnancy disorders have to be included as an independent variable in cardiovascular risk prediction models for women to improve their assessment of reliable cardiovascular risk estimation for the long term CVD outcome. Strengths and limitations The major strength of this longitudinal follow-up study is that we used a unique prospective cohort from a randomized controlled trial, which consisted of women with a history of term gestational hypertension or term preeclampsia. Hypertensive pregnancy disorders at term are common disorders and therefore of great interest for health care providers. These disorders may be used as a discriminating test whether or not the clinician has to screen for cardiovascular risk factors and calculate subsequent individual cardiovascular risk.

This study has also potential limitations. First, due to the young age of our study participants, 10-year overall cardiovascular disease risk in our cohort was. In conclusion, women with a history of gestational hypertension or preeclampsia at term have higher (extrapolated) 10-year cardiovascular event risks and 30-year cardiovascular event risks compared with women with a history of uncomplicated pregnancies. Our study results strongly suggest that women with a history of hypertensive pregnancy disorders at term may be offered screening and counseling for cardiovascular risk factors after their pregnancy to calculate and estimate cardiovascular event risks. Details of ethics approval The HyRAS and HYPITAT studies were approved both primarily for all participating hospitals in the Netherlands by the medical ethics committee of Leiden University Medical Center (HYPITATP04.210) and locally by the hospital board of the participating hospitals. The clinical trial registration number of the HYPITAT trial is: ISRCTN08132825.

Acknowledgements We thank all the research nurses and research midwives from the Dutch Obstetric Consortium for their enthusiastic efforts in recruitment, data acquisition and data recording. Clara Kolster is acknowledged for her contribution to the study. Funding Wietske Hermes is currently supported by a non-commercial grant from the Landsteiner Institute, Medical Center Haaglanden, The Hague, the Netherlands and by the Nuts Ohra Foundation, the Netherlands. For the remaining authors none were declared. Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions WH, JT, AF, JP, MP, KB, MP, BM, and CG designed the study. WH, MVP, KB, JP, MP, BM and CG participated in acquisition of data. WH, DG, JT, BM, and CG analyzed and interpretated the data. WH, DG, JT, BM and CG drafted the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Supplementary material.